So many physical abilities decline with normal aging, including strength, swiftness, and stamina. In addition to these muscle-related declines, there are also changes that occur in coordinating the movements of the body. Together, these changes mean that as you age, you may not be able to perform activities such as running to catch a bus, walking around the garden, carrying groceries into the house, keeping your balance on a slippery surface, or playing catch with your grandchildren as well as you used to. But do these activities have to deteriorate? Let’s look at why these declines happen — and what you can do to actually improve your strength and coordination.

Changes in strength

Changes in strength, swiftness, and stamina with age are all associated with decreasing muscle mass. Although there is not much decline in your muscles between ages 20 and 40, after age 40 there can be a decline of 1% to 2% per year in lean body mass and 1.5% to 5% per year in strength.

The loss of muscle mass is related to both a reduced number of muscle fibers and a reduction in fiber size. If the fibers become too small, they die. Fast-twitch muscle fibers shrink and die more rapidly than others, leading to a loss of muscle speed. In addition, the capacity for muscles to undergo repair also diminishes with age. One cause of these changes is decline in muscle-building hormones and growth factors including testosterone, estrogen, dehydroepiandrosterone (better known as DHEA), growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor.

Changes in coordination

Changes in coordination are less related to muscles and more related to the brain and nervous system. Multiple brain centers need to be, well, coordinated to allow you to do everything from hitting a golf ball to keeping a coffee cup steady as you walk across a room. This means that the wiring of the brain, the so-called white matter that connects the different brain regions, is crucial.

Unfortunately, most people in our society over age 60 who eat a western diet and don’t get enough exercise have some tiny "ministrokes" (also called microvascular or small vessel disease) in their white matter. Although the strokes are so small that they are not noticeable when they occur, they can disrupt the connections between important brain coordination centers such as the frontal lobe (which directs movements) and the cerebellum (which provides on-the-fly corrections to those movements as needed).

In addition, losing dopamine-producing cells is common as you get older, which can slow down your movements and reduce your coordination, so even if you don’t develop Parkinson’s disease, many people develop some of the abnormalities in movement seen in Parkinson's.

Lastly, changes in vision — the "eye" side of hand-eye coordination — are also important. Eye diseases are much more common in older adults, including cataracts, glaucoma, and macular degeneration. In addition, mild difficulty seeing can be the first sign of cognitive disorders of aging, including Lewy body disease and Alzheimer’s.

How to improve your strength and coordination

It turns out that one of the most important causes of reduced strength and coordination with aging is simply reduced levels of physical activity. There is a myth in our society that it is fine to do progressively less exercise the older you get. The truth is just the opposite! As you age, it becomes more important to exercise regularly — perhaps even increasing the amount of time you spend exercising to compensate for bodily changes in hormones and other factors that you cannot control. The good news is that participating in exercises to improve strength and coordination can help people of any age. (Note, however, that you may need to be more careful with your exercise activities as you age to prevent injuries. If you’re not sure what the best types of exercises are for you, ask your doctor or a physical therapist.)

Here are some things you can do to improve your strength and coordination, whether you are 18 or 88 years old:

- Participate in aerobic exercise such as brisk walking, jogging, biking, swimming, or aerobic classes at least 30 minutes per day, five days per week.

- Participate in exercise that helps with strength, balance, and flexibility at least two hours per week, such as yoga, tai chi, Pilates, and isometric weightlifting.

- Practice sports that you want to improve at, such as golf, tennis, and basketball.

- Take advantage of lessons from teachers and advice from coaches and trainers to improve your exercise skills.

- Work with your doctor to treat diseases that can interfere with your ability to exercise, including orthopedic injuries, cataracts and other eye problems, and Parkinson’s and other movement disorders.

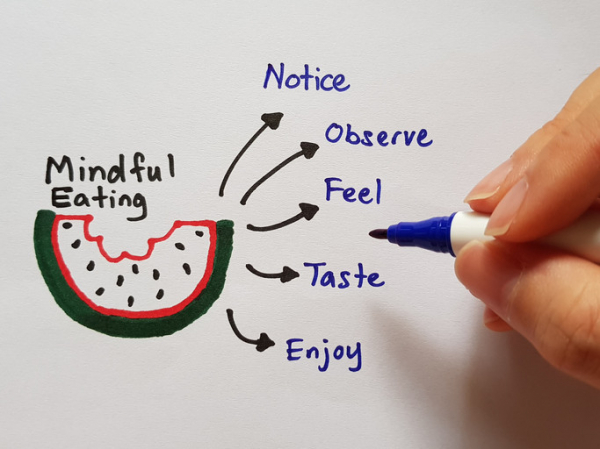

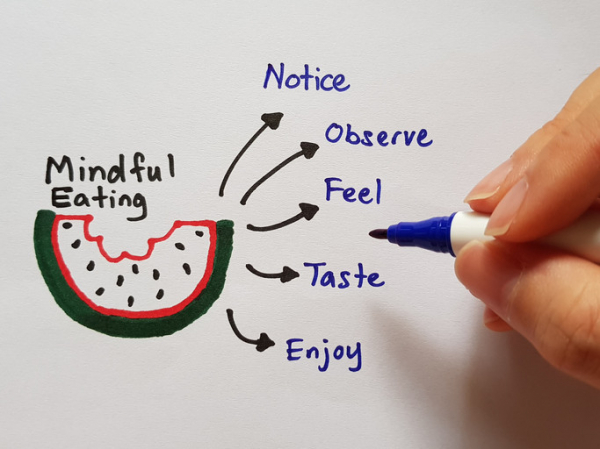

- Fuel your brain and muscles with a Mediterranean menu of foods including fish, olive oil, avocados, fruits, vegetables, nuts, beans, whole grains, and poultry. Eat other foods sparingly.

- Sleep well — you can actually improve your skills overnight while you are sleeping.

About the Author

Andrew E. Budson, MD, Contributor

Dr. Andrew E. Budson is chief of cognitive & behavioral neurology at the Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, lecturer in neurology at Harvard Medical School, and chair of the Science of Learning Innovation Group at the Harvard Medical School Academy. Graduating cum laude from Harvard Medical School in 1993, he has given over 650 local, national, and international grand rounds and other talks; published over 100 scientific papers, reviews, and book chapters; and co-authored or edited seven books. His book Seven Steps to Managing Your Memory: What’s Normal, What’s Not, and What to Do About It explains how individuals can distinguish changes in memory due to Alzheimer’s versus normal aging; what medications, vitamins, diets, and exercise regimes can help; and the best habits, strategies, and memory aids to use; it is being translated into Chinese and Korean. His book Memory Loss, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Dementia: A Practical Guide for Clinicians has been translated into Spanish, Portuguese, and Japanese. His latest book, Six Steps to Managing Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia: A Guide for Families teaches caregivers how they can manage all the problems that come with dementia—and still take care of themselves. Website: Andrew Budson, MD Facebook: Andrew Budson, MD Twitter: @abudson View all posts by Andrew E. Budson, MD