Let’s face it: inflammation has a bad reputation. Much of it is well-deserved. After all, long-term inflammation contributes to chronic illnesses and deaths. If you just relied on headlines for health information, you might think that stamping out inflammation would eliminate cardiovascular disease, cancer, dementia, and perhaps aging itself. Unfortunately, that’s not true.

Still, our understanding of how chronic inflammation can impair health has expanded dramatically in recent years. And with this understanding come three common questions: Could I have inflammation without knowing it? How can I find out if I do? Are there tests for inflammation? Indeed, there are.

Testing for inflammation

A number of well-established tests to detect inflammation are commonly used in medical care. But it’s important to note these tests can’t distinguish between acute inflammation, which might develop with a cold, pneumonia, or an injury, and the more damaging chronic inflammation that may accompany diabetes, obesity, or an autoimmune disease, among other conditions. Understanding the difference between acute and chronic inflammation is important.

These are four of the most common tests for inflammation:

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (sed rate or ESR). This test measures how fast red blood cells settle to the bottom of a vertical tube of blood. When inflammation is present the red blood cells fall faster, as higher amounts of proteins in the blood make those cells clump together. While ranges vary by lab, a normal result is typically 20 mm/hr or less, while a value over 100 mm/hr is quite high.

- C-reactive protein (CRP). This protein made in the liver tends to rise when inflammation is present. A normal value is less than 3 mg/L. A value over 3 mg/L is often used to identify an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, but bodywide inflammation can make CRP rise to 100 mg/L or more.

- Ferritin. This is a blood protein that reflects the amount of iron stored in the body. It’s most often ordered to evaluate whether an anemic person is iron-deficient, in which case ferritin levels are low. Or, if there is too much iron in the body, ferritin levels may be high. But ferritin levels also rise when inflammation is present. Normal results vary by lab and tend to be a bit higher in men, but a typical normal range is 20 to 200 mcg/L.

- Fibrinogen. While this protein is most commonly measured to evaluate the status of the blood clotting system, its levels tend to rise when inflammation is present. A normal fibrinogen level is 200 to 400 mg/dL.

Are tests for inflammation useful?

In certain situations, tests to measure inflammation can be quite helpful.

- Diagnosing an inflammatory condition. One example of this is a rare condition called giant cell arteritis, in which the ESR is nearly always elevated. If symptoms such as new, severe headache and jaw pain suggest that a person may have this disease, an elevated ESR can increase the suspicion that the disease is present, while a normal ESR argues against this diagnosis.

- Monitoring an inflammatory condition. When someone has rheumatoid arthritis, for example, ESR or CRP (or both tests) help determine how active the disease is and how well treatment is working.

None of these tests is perfect. Sometimes false negative results occur when inflammation actually is present. False positive results may occur when abnormal test results suggest inflammation even when none is present.

Should you be routinely tested for inflammation?

Currently, tests of inflammation are not a part of routine medical care for all adults, and expert guidelines do not recommend them.

CRP testing to assess cardiac risk is encouraged to help decide whether preventive treatment is appropriate for some people (such as those with a risk of a heart attack that is intermediate — that is, neither high nor low). However, evidence suggests that CRP testing adds relatively little to assessment using standard risk factors, such as a history of hypertension, diabetes, smoking, high cholesterol, and positive family history of heart disease.

So far, only one group I know of recommends routine testing for inflammation for all without a specific reason: companies selling inflammation tests directly to consumers.

Inflammation may be silent — so why not test?

It’s true that chronic inflammation may not cause specific symptoms. But looking for evidence of inflammation through a blood test without any sense of why it might be there is much less helpful than having routine healthcare that screens for common causes of silent inflammation, including

- excess weight

- diabetes

- cardiovascular disease (including heart attacks and stroke)

- hepatitis C and other chronic infections

- autoimmune disease.

Standard medical evaluation for most of these conditions does not require testing for inflammation. And your medical team can recommend the right treatments if you do have one of these conditions.

The bottom line

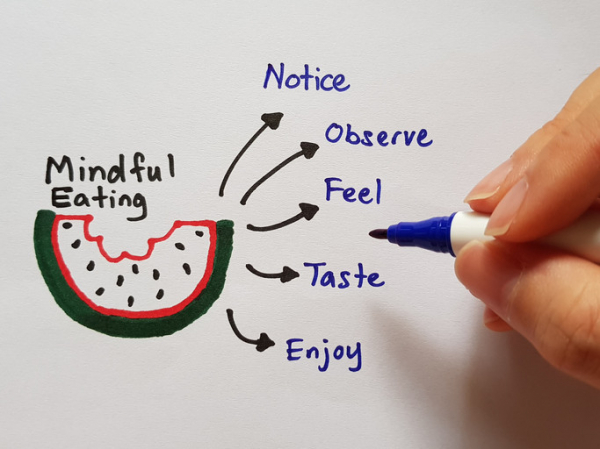

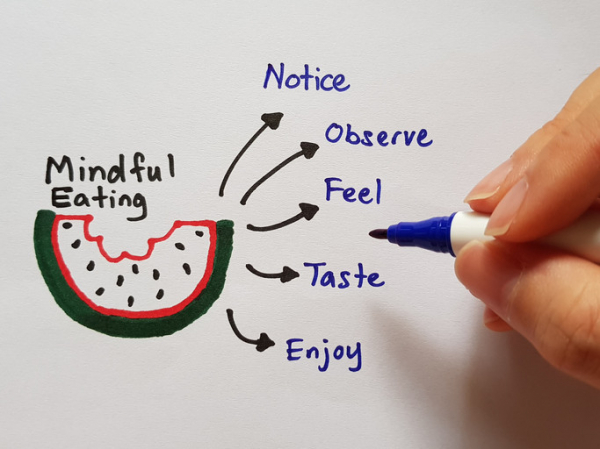

Testing for inflammation has its place in medical evaluation and in monitoring certain health conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis. But it’s not clearly helpful as a routine test for everyone. A better approach is to adopt healthy habits and get routine medical care that can identify and treat the conditions that contribute to harmful inflammation.

About the Author

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Robert H. Shmerling is the former clinical chief of the division of rheumatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), and is a current member of the corresponding faculty in medicine at Harvard Medical School. As a practicing rheumatologist for over 30 years, Dr. Shmerling engaged in a mix of patient care, teaching, and research. His research interests center on diagnostic studies in patients with musculoskeletal symptoms, and rheumatic and autoimmune diseases. He has published research regarding infectious arthritis, medical ethics, and diagnostic test performance in rheumatic disease. Having retired from patient care in 2019, Dr. Shmerling now works as a senior faculty editor for Harvard Health Publishing. View all posts by Robert H. Shmerling, MD